This is Meredith Rose’s first blog post in her series on copyright and cosplay. Ask her your questions about fandom and the law at publicknowledge.org/AskALegalNerd.

One of the questions about copyright that comes up most often at fan conventions is whether or not cosplay is “legal.” It’s a good question, but it gets into some of the murkiest areas of copyright law.

Before we dive in, a disclaimer and a preface. First, I am not your lawyer. Nothing in here is legal advice. Please don’t send me photos of your cosplay and ask me for analysis.

Second, an important a reality check: cosplay isn’t going anywhere soon. Rightsholders have so far embraced — and even promoted — the art form, as it’s a good meter stick for audience engagement (and free advertising to boot).

All of which is to say, there’s no need to burn your wigs and destroy your sewing machine. There are factors, both legal and otherwise, that make it unlikely — but not impossible — for a rightsholder to start suing cosplayers.

This blog is a largely theoretical exercise. The legal system has never directly addressed cosplay as we generally think of it. (It has, however, had some delightfully weird near-misses, like banana suits and inflatable mascot costumes of Cap’n Crunch.) Because of that, there are no settled answers. Instead, this blog post is an attempt to take broad, abstract, arcane legal principles and see what they might say about cosplay, if given the chance.

What does copyright law say…?

…About characters?

Statutory copyright law (the stuff that is written down in the U.S. Code) protects “works” — discrete novels, films, computer programs, or other media. This is because when you start to zoom in closely on each constituent part of a work — plot structure, setting, character — they start to look less and less original.

Take Star Wars. While we all recognize A New Hope as an original piece of authorship, the constituent parts of its story, taken by themselves, look pretty standard: Jungian archetypes reenact the hero’s journey, all against a narrative and visual structure largely drawn from the work of Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa. This is nothing new, and it’s not unique to George Lucas. Storytellers have used stock characters, formulaic plots, and tropes since the first cro-magnons gathered around a fire. The law correctly recognizes that these tropes are part of our shared narrative language, and granting ownership of them to whoever used them last would hobble our ability to tell stories.

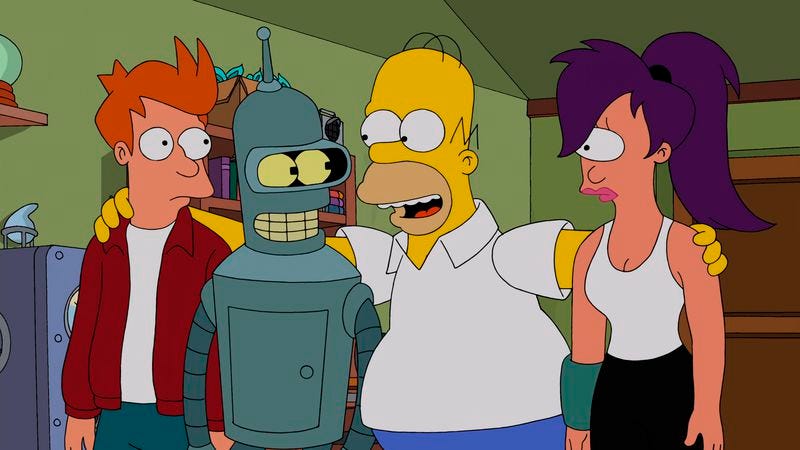

Not every character is a stock character, however. Courts have recognized that some characters might be original enough to deserve their own copyright protection, separate from the copyright that protects the work in which they appear. There’s no clear test for this (despite decades of judicial fights over the topic), but the rule of thumb is that the more unique or well-developed the character, the stronger the copyright protection. (Characters from visual media get an extra leg up here, because their visual distinctiveness makes them less “generic.”) They carry this copyright no matter what work they appear in; Fox holds a copyright in Bart Simpson, whether he’s on his own show or making a cameo on South Park.

This is true even if that character has gone through multiple “incarnations,” so long as the core of the character remains the same. James Bond got the character copyright treatment, with the district court citing “his cold-bloodedness; his overt sexuality; his love of martinis ‘shaken, not stirred;’ his marksmanship; his ‘license to kill’ and use of guns; his physical strength; [and] his sophistication” as defining characteristics.

…About fashion and clothing copyright?

On the left, Oleg Cassini’s design sketch; on the right, Jackie Kennedy in the finished suit. (Noble y Real)

Before getting into the tangle of clothing copyright, we need to step back and remember what copyright does and does not protect. Copyright is designed to protect expressive works (drawings, sculpture, writing, etc). It does not protect functional objects (headphones, frying pans, pens, etc).

This distinction gets fuzzy around the edges, as we’ve written before; functional objects often have expressive design elements, and it’s not always easy to figure out where unprotected “function” ends and protected “form” begins.

After decades of courts tying themselves in knots trying to figure out how to separate out protectable and non-protectable elements of the same work, the Supreme Court took up a case (in which Public Knowledge filed an amicus brief) to finally lay down an answer. While it didn’t clarify much, the Court did provide a new two-part test. A design element in a functional object is entitled to protection if it “(1) can be perceived as a two- or three-dimensional work of art separate from the useful article and (2) would qualify as a protectable pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work either on its own or in some other medium if imagined separately from the useful article.”

Throughout this, courts have gone out of their way to treat clothing as a functional item. The reasons why are many and varied, but this status quo — that clothing design isn’t protectable under copyright law — has allowed “fast fashion” chains like H&M, Forever 21, and the Gap to produce low-cost versions of runway designs for millions of consumers. High-fashion industries have pushed a couple of times to create a new, separate protection for clothing design, but all attempts so far have failed.

The end result is that, while an image of clothing (such as a painting, or design sketch) might be protectable by copyright, the clothing itself — the real, wearable item — is not.

How does all of this apply to cosplay?

Who are you copying?

Remember that unique characters may be copyright protected, and characters with a distinct visual representation (such as a superhero) are more protectable than those without (such as a character in a book). If the character has been visually represented, the fewer costumes a character has, the more any given costume will be indelibly associated with the character — thus, the more directly that character’s copyright is implicated.

Cosplay is, in essence, the act of reproducing that character, with yourself as the canvas. More than any other area of the law, it most directly impacts the copyright of a character itself, rather than the work around it.

What are you copying?

Props, armor, etc:

First disclaimer: props, armor, accessories, and other things that aren’t “traditionally” clothing (such as jewelry, replica weapons, and the like) don’t fit under these schema; for the purposes of copyright law, they’re considered sculptural works. This is true even of armor — remember how courts hinge their definition of clothing as being “functional”? Your Mandalorian armor may stylish, but it doesn’t have a function beyond decoration.

Costumes from live-action media:

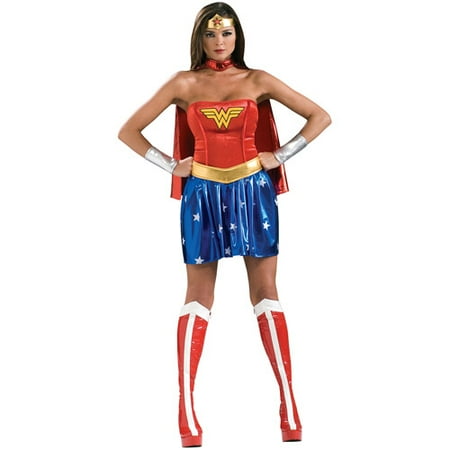

Generally, because clothing design is not covered by copyright, cosplay doesn’t have anything to infringe upon — because there’s no copyright to protect. This does have some weak points; Specific designs printed on the clothing — such as Superman’s iconic “S,” or the black-and-yellow chevron pattern of Charlie Brown’s shirt — may independently be subject to copyright, and replicating them could constitute infringement.

Non-live-action media:

Remember that while clothing doesn’t (generally) have copyright protection, artistic representations — such as drawings, 3D modeling, and paintings — of clothing do. To give an example, while Jackie Kennedy’s famous red wool day suit is not copyrightable, Oleg Cassini’s design drawing of it is.

This means that if what you’re copying isn’t a physical piece of clothing in the real world, but only an image of clothing, it may in fact be a derivative work of a copyrighted property.

But is it fair use?

Fair use is intensely fact-specific. Because of this, it’s impossible to say categorically whether cosplay is or is not fair use. What we can do is apply the same legal analysis that courts use, to see how cosplay shakes out.

Fair use is a “four-factor test,” meaning that courts look at four (or more) aspects of the use, and balance these considerations to arrive at a conclusion. The elements that courts examine are (1) the purpose and character of the use, (2) the nature of the copyrighted work, (3) The amount and substantiality of the portion taken, and (4) the potential effect of the use upon the market for the original.

The purpose and character of the use

It’s impossible to count the number of hours lawyers have spent arguing over what “the purpose and character of the use” factor actually means. For the sake of simplicity (and sanity), we’ll focus on the two parts most relevant to fan activity: money, and something called “transformativeness.”

When you ask people about fandom activities and the law, their immediate response is usually some form of “well, as long as they’re not making any money off of it.” This is simultaneously intuitively true, and legally false. You don’t have to be making money to run afoul of copyright law. While for-profit uses do not immediately lose the fair use argument, they do have a harder time in the overall analysis. One of the most famous fair use cases, Campbell v. Acuff-Rose, found that a for-profit song was a parody protected under fair use, even though the “users” were making money off of it. So while it’s not impossible to be making money and be a fair use, it is a bit harder to convince the court of your position.

Another thing the court asks is whether the new work uses the source material in new and interesting ways — also known as its “transformativeness.” Works that are very transformative — that take the source material and make something new and highly original — get a lot of weight under this factor. A mere “change in format” (such as taking a photograph and turning it into a sculpture), however, is usually not enough, by itself, to be transformative.

In other words, making a faithful, real-life replica of an imaginary outfit is likely not “transformative” enough to win this prong. But, like all things, cosplay exists on a sliding scale; mashup and crossover cosplay puts a new spin on the source material, and is therefore farther along the transformative spectrum than straight replication.

The nature of the copyrighted work & the amount and substantiality of the portion taken

Try not to take more than needed.

These two factors generally get glossed over (much like your eyes, at this point). For these, the court examines what kind of work — fiction or nonfiction, print or visual, critical or creative — the original was, and how much of it made it into the new work. Cosplay generally recreates only a small proportion of its source work (you can’t cosplay as the entire Mass Effect trilogy, though I’d love to see someone try). However, the source works are generally highly creative, fictional worlds. Given that both factors are equally elided over, these two prongs come out in the wash.

The effect of the use upon the potential market

In the last step of a fair use analysis, the court asks, “is this new use going to displace the market for the original?” Generally speaking, it is unlikely that your cosplay will negatively impact the number of people buying the source material (in fact, it may even provide free advertising in the right setting). One-offs that don’t displace an existing market or deprive the rightsholder of revenue opportunities are generally seen as economically harmless, meaning they get a good amount of leeway under this prong.

The only folks who may run afoul of this prong are those that are making and selling cosplay to other people, and doing so at scale. It’s not a stretch to argue that these people might be displacing the market for official, licensed costumes.

On the other hand, you can argue that there are really two different kinds of buyers (and thus, two different markets). The person who wants the Halloween costume would never drop hundreds of dollars on a custom tailored leather Wonder Woman bustier, and someone interested in a high-quality, Comic Con-ready replica isn’t going to settle for the packaged Halloween costume.

Unfortunately, courts generally look askance at these kinds of arguments, instead reasoning that, even if they’re not currently making high-quality reproductions, rightsholders should retain the option to do so without unlicensed competition impeding their way. So if you’re making and selling unlicensed cosplay, you’re likely out of luck on this prong.

In Conclusion

Copyright is a hugely important but very often arcane area of the law that doesn’t always go where you’d expect it to. We’re lucky to be living in a time where fandom generally enjoys a positive relationship with the creators whose work it admires (though this has not always been the case). Cosplay isn’t going anywhere — and if it is, it has a long and complicated legal status to unpack first.

Top image credit: Alan Light